When it comes to mishandling Scripture, few people can match the death-defying logical leaps of biblical daredevil Joseph Prince. Pastor of Singapore megachurch New Creation Church, Prince has been invited to speak at various Hillsongs conferences and Joel Osteen’s Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas. His television show, Destined to Reign, reaches millions daily.

When it comes to mishandling Scripture, few people can match the death-defying logical leaps of biblical daredevil Joseph Prince. Pastor of Singapore megachurch New Creation Church, Prince has been invited to speak at various Hillsongs conferences and Joel Osteen’s Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas. His television show, Destined to Reign, reaches millions daily.

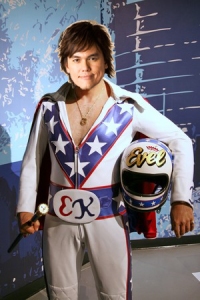

What makes a pastor such a coveted international speaker? Sound, grammatical-historical biblical interpretation, you say? No. That would be boring. What people really want is an approach to Scripture that makes the Bible seem like a puzzle book with “Jabez Prayer”-like secrets waiting to be unlocked by the newest hermeneutical Evel Knievel.

Here’s an excerpt from one of this week’s devotional gems at JosephPrinceonline.com:

“And the Child grew and became strong in spirit, filled with wisdom; and the grace of God was upon Him.” Luke 2:40

The verse says that the grace of God was upon Jesus. The Bible also says that where sin abounds, grace abounds much more. (Romans 5:20) And when you put the two together, you may find yourself asking, “If the grace of God was upon Jesus, does it mean that He sinned?”

No, Jesus did not sin. (2 Corinthians 5:21) So there must be another explanation as to why God’s grace was upon Jesus. There must be another explanation as to why someone can abound in God’s grace even when he has not sinned.

Let’s look at the word “grace” when it is first mentioned in the Bible. Genesis 6:8 says that “Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord”. Noah’s name means “rest”. So the verse is telling us that rest found grace. In other words, when you rest, you find grace!

So grace was upon Jesus because His life was a life of rest and trust in His Father.

Let’s watch that again in slow motion.

Noah’s name means rest.

Noah found grace.

Therefore, rest found grace.

Therefore, if we rest, we will find grace.

See how easy that was? No need for those expensive Bible commentaries and long hours studying Hebrew. All you need is a Hebrew name book. Let’s try some ourselves.

Esau means hairy.

In Malachi 1, God says, “I have loved Jacob, but Esau I have hated…”

Therefore, God hates hairy people.

Let’s try a Noah one.

Noah means rest.

After the flood, Noah got drunk and exposed himself.

Therefore, when we rest, we should get drunk and … hmm … perhaps this is one of those “don’t try this at home” interpretive stunts.

Good exegesis is hard. It requires lots of study and knowledge of the original languages, culture and context. Perhaps it’s not surprising that Joseph Prince, the author of Destined to Reign: The Secret to Effortless Success, Wholeness and Victorious Living, prefers an easier hermeneutical approach.

Effortless indeed.

Charisma magazine profiled Prince last year. It would seem that Prince’s interpretive approach lends itself to a word-of-faith type message. The article quotes Prince’s book, Unmerited Favor:

Because of the cross, we can today expect good, we can expect success, we can expect promotion, increase and the abundant life. It is all because of our wonderful Lord Jesus. If we have Him, we have everything and more, and can be a blessing to others.

His message is, predictably, popular in the U.S., where his televised services are broadcast on TBN, ABC Family Channel and several other networks. Charisma quotes one enthused viewer:

Linda Lee Bingham of New Jersey said understanding grace has enabled her to better trust and rest in God. “Good things are popping into my life faster than I can imagine,” she says. “I started a new business project a few months ago and already have 10 employees. The work is finished on the cross, and I’m just enjoying the ride.”

That’s right Linda Lee. Jesus bled on the cross so that you could get your Amway business off the ground. PTL!

To get a real flavor for the interpretive stylings of Joseph Prince, check out the video below. Skip ahead to the 9:00 minute mark to learn:

- that Luke 21:25-26 contains a prediction of the March 2011 Japanese tsunami and nuclear crisis;

- that ouranos [misspelled uranos by Prince] is the ancient Greek word for uranium [an element first discovered in 1789 AD]; and

- that taking communion will neutralize the radiation in your body from the Japanese nuclear leak.

Can’t get enough Prince? In this next video, Prince explains how the book of Deuteronomy and the cartoonish map in the back of his Bible enabled him to predict the discovery of an offshore natural gas deposit near (actually, nowhere near) Haifa.

Kind of makes Harold Camping look like a top-notch biblical scholar, doesn’t he?

If you’ve spent any time in evangelical circles, you’ll be familiar with certain guilt-inducing analogies about evangelism. Not telling your neighbor about Jesus is like not throwing a life preserver to a drowning man. Not sharing the gospel with your school chum is like having the cure for cancer and not sharing it with a cancer-stricken friend.

If you’ve spent any time in evangelical circles, you’ll be familiar with certain guilt-inducing analogies about evangelism. Not telling your neighbor about Jesus is like not throwing a life preserver to a drowning man. Not sharing the gospel with your school chum is like having the cure for cancer and not sharing it with a cancer-stricken friend. Comfort eventually gets his interviewees to admit that they are guilty of breaking God’s law. He then asks whether God will send them to heaven or hell as a consequence of such guilt. People tend to divide down the line on this one. Some say “hell”, though often with a laugh, suggesting that they don’t really believe this to be their fate. Others insist that they will still go to heaven because they aren’t bad people. This is when it gets interesting. Comfort must then persuade these people that they are deserving of eternal torment, often on the basis of their having admitted to little more than telling lies and “looking at a women with lust.”

Comfort eventually gets his interviewees to admit that they are guilty of breaking God’s law. He then asks whether God will send them to heaven or hell as a consequence of such guilt. People tend to divide down the line on this one. Some say “hell”, though often with a laugh, suggesting that they don’t really believe this to be their fate. Others insist that they will still go to heaven because they aren’t bad people. This is when it gets interesting. Comfort must then persuade these people that they are deserving of eternal torment, often on the basis of their having admitted to little more than telling lies and “looking at a women with lust.” I was reminded of Comfort this week while watching N.T. Wright’s recent talks at Moody Bible Institute. Wright spent a good deal of time sketching the framework for a proper narrative understanding of the gospel in its first century Jewish context. Christ “saving his people from their sins,” he maintains, is primarily about Christ’s role as Savior of the Jewish people from exile (i.e. from the consequences of their corporate sin). For the New Testament authors, “salvation” was about God rescuing his people. It meant the restoration of the Jewish nation – indeed, all of creation – and of individuals as part of that corporate restoration.

I was reminded of Comfort this week while watching N.T. Wright’s recent talks at Moody Bible Institute. Wright spent a good deal of time sketching the framework for a proper narrative understanding of the gospel in its first century Jewish context. Christ “saving his people from their sins,” he maintains, is primarily about Christ’s role as Savior of the Jewish people from exile (i.e. from the consequences of their corporate sin). For the New Testament authors, “salvation” was about God rescuing his people. It meant the restoration of the Jewish nation – indeed, all of creation – and of individuals as part of that corporate restoration.

The Pastoral epistles describe travels of Paul that bear little resemblance to what we know of his journeys from Acts and other Pauline letters. They have Paul ministering in Crete and leaving Titus to continue the work they had begun. They have Paul wintering in Nicopolis (Western Greece). They have Paul leaving Timothy in Ephesus when he departs for Macedonia (seemingly contrary to Acts 20 which says that Timothy was Paul’s companion on his journey from Ephesus into Macedonia and Greece).

The Pastoral epistles describe travels of Paul that bear little resemblance to what we know of his journeys from Acts and other Pauline letters. They have Paul ministering in Crete and leaving Titus to continue the work they had begun. They have Paul wintering in Nicopolis (Western Greece). They have Paul leaving Timothy in Ephesus when he departs for Macedonia (seemingly contrary to Acts 20 which says that Timothy was Paul’s companion on his journey from Ephesus into Macedonia and Greece).

In

In